THE MAGICIAN'S CLOAK

Essay by James Waller

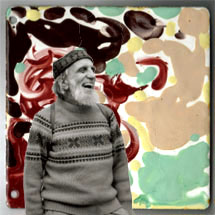

On the art of Icilio Martich Severi (1920 - 1999)

To approach a shroud, one must as Severi once said, come: "on tiptoe, not on Nazi boots".1 How, then must the shroud maker be? The fantasist creates a raiment from sunlight, which in turn takes on the reflection of the moon. In 1953 Severi composed Sorcerer in coloured pencil. It is both shroud and the creation of the shroud, a contemporary refraction of Velasquez's masterpiece Les Maninas, or Gauguin's Magician of Havoa.

Sorcerer is a contemporary work of art, in its choice of material and in its resolution. Its resolution represents the disintegration of reality, not in any cubist sense, but in its totally ambiguous state of becoming. Within its trembling and thirsting light one may sense the future unfolding of Severi's raiment. One may also feel the following words which Vincenzo Aurigemma quoted in 1950:

| Through the "fantastic transfiguration of reality (according to F De Sanctis), A complete abandonment of reality takes place."2 |

Like Breughel in an earlier epoch and Borges in his own, Severi's fantasy takes on the haunting and wondrous revelation of life. It is in its ambiguous state of becoming that Sorcerer renders fabric unto fabric, the point of simultaneous becoming and collapsing, all under the spell of the gentle weaver of light.

Sorcerer, like the moon, is bathed in both light and dark. Unlike the moon it projects both from itself; its cloak of colour struggles, as from bonds, towards Severi's felt pens of 1987 and the earlier fibreglass works of the 1960s. In contrast, the shroud's lining glistens in the dark of the biros from 1956.

The profound sense of simultaneous collapse and creation shown in Sorcerer is a point Severi reaches time and again throughout his oeuvre. What , one must ask, is the depth of this discovery? In the presence of the great works of Giccometti one is left with a sense of pure matter - the tortured growth into death of matter - only matched in painting by the rendering of El Greco.

One senses Severi constantly leaning towards this deep spiritual state. This leaning is revealed in the artist's point of creation and collapse, which is reached most fully in the small powerful biros dating from 1956. Occasionally in these biros "growth into death" is revealed in all its startling infinity. But is this the essence of Severi?

1

1Just as his art reaches these dark spaces, in the next form one finds Severi buoyed up as a song of light. This is the light which emanates from Sorcerer, which occasionally reaches such a state of satori that one is tempted to look no further. I speak of Severi's felt pen form which was developed as early as the 1960s and which exists in several basic sub-forms. The form I am concerned with here is represented by an untitled composition from 1987, which I shall name for convenience Sator. Sator embodies, more than any of Severi's other work, the profound sense of satori which exists in contra to the dark writhing biros of the earlier period.

2

2The work dwells in five compositional rings. Its appearance is of these rings broken up into magical spires. With time one becomes aware of its profound sculptural essence, as if the sound structure of a bird song had been sculpted from the air, revealed in light and pressed upon the paper. Only one is not aware of paper or plane; the paper has become an infinite chamber of white light, and the plane rendered invisible. One is no longer aware of the immanent collapse prevalent in Sorcerer and the 1956 biros. Sator is a living dance of spiritual balance and silence.

Within Sator and its companion compositions one finds the true enigman , the riddler of light, the pray-er of sunrise. Formally they are astonishing creations, achieving something similar to haiku in poetry i.e. the poetic compression of space.

In terms of compositional inventiveness Severi far outstrips his contemporaries. For all the intensity and contemporaniety of Leonard French his compositions look convoluted in comparison. And while Stan Ostoja-Kotkowski was an optical inventor, his science never touched the compositional discoveries Severi's poetry achieved.

This poetry was brought most beautifully to life in the late 1960s in the form of six large fibre glass panels. Four of these panels remain installed in Severi's Camperdown studio and glow as shrouds of their creator, in genuflection to creation itself. It is often commented by family and friends that Severi used what was around him and what he could obtain within the strict limitations of his finances. Can anyone truly comprehend the hardship and spiritual suffering of the true creative artist? Michaelangelo wrote, "No one stops to think how much blood it costs."3 Where sublimation is frozen into matter there is the work of art. Where possibilities are frozen by history there is a life. Would Severi have made more of these panels given the means? Who can say? What is truly remarkable is the spiritual harmony arising from within the artist, and appearing as the ancient magical ruins of painting itself. How much blood did it cost? How much suffering and awareness to reach this point? An act of genuflection is no small thing. It must be aware of what nature is.

3

3The question of whether Severi might have continued his work in fibre glass leads us to a fascinating aspect of the artist's nature. As early as 1950 Vincenzo Aurigemma wrote:

Severi likes to change his medium of expression; he moves freely from clay to paint to ink. He loves them all and distrusts them equally in his faithful search for a technique as free as his inspiration. 4

Severi's insatiable desire for fresh material may have precluded further fibre glass work inspite of his financial status. Certainly Aurigemma's words hold true forty years on: where most artists narrow their range of specialty, Severi actually expanded. It is as if the spirit of the artist refused to be caught, refused to be seduced by matter, as if his fantasy remained alive in the polyphony of material rather than the monopoly of one. This sets Severi at odds with artists like Georgio Morandi, whose fidelity to a singular subject and medium is unparalleled. It is an interesting comparison, as Morandi evokes a similar spirit to Severi at his most serene in his fibre glass panels.

The compression of space, begun in the melted light of Sorcerer in 1953, creates a new space in art. This alone should secure Severi's place in history. The spirit emanating from this compression, most completely achieved in fibre glass, resolves and transcends Sorcerer of 1953 and acts in counterpoint to the biros from 1956. It is as if "Sator" of 1987 gathers up the liquid magic of Sorcerer and respells it in crystal and singing clarity.

This is the work of a magician who reconfigured his cloak according to the movement of his soul. Severi clarifies, more than any other painter, what painting is, by revealing its ruins: a mysterious arrangement, a syntax which speaks.

Between the works in pencil, biro, felt pen and fibre glass (by no means an exhaustive list) one senses the range of Severi's spiritual confrontation. It is a confrontation which engages with the darkness of being, in a spirit which is distinctly his own, whilst conjuring the distant ghosts of Gioccometti and ElGreco. It is also a confrontation which rises to being's very lightness, in a form which is truly astonishing. It echoes the world of haiku and the inner landscape of Morandi. Confronted with his work one is touched by a unique syntax: that of the magician's cloak.

1. Art and Artists as Social Phenomena, p. 29.

2. ibid (translation from exhibition catalogue Venice 1950), p. 19.

3. Michaelangelo, The Poems, p. 1.

4. Art and Artists as Social Phenomena, p. 19.

2 "Sator" 1987 ibid

3. Fibre Glass Screen - Icilio's Studio, the Severi Estate. Level 1, 16 Marsden Street, Camperdown, NSW, Australia, on +61 2 9660 5131 or fax: +61 2 9552 4592.

Page design © Art News 2000